why teen brains are more vulnerable to fentanyl and opioid addiction

the opioid crisis in canada is not just a street problem — kids from seemingly well-to-do homes homes are overdosing in starbucks bathrooms

cameron shaver died of an overdose

at 23, cameron shaver seemed to be on track for success with a landscaping business, a new car, and he was thinking about heading back to school to take culinary arts.the jack-of-all-trades from winnipeg was an inspiration to his friends. he’d come a long way from his earlier teen years, when he had struggled with drug addiction. back then, it was ecstasy.cameron had been clean for years when, last september, his mother sandi received the phone call that no mother should get. cameron had died of a fentanyl overdose.“that’s not how his life was supposed to go,” she said. “you aren’t supposed to bury your child. how do these dealers not know these drugs are killing our kids?”fentanyl is a parent’s worst nightmare. the opioid crisis in canada is not just a street problem — kids from seemingly good homes are overdosing in starbucks bathrooms and ending up in hospital emergency rooms.this past valentine’s day, 14-year-old chloe kotval died from a fentanyl overdose in ottawa. and last month, the b.c. coroner’s office found that the august death of 16-year-old gwyn kenny-staddon in a starbucks bathroom in port moody was from an overdose of heroin and fentanyl.last november, the canadian institute for health information reported that youth aged 15 to 24 experienced a 62 per cent increase in hospitalizations for opioid use since 2007. this represents the fastest increase of any age group.

advertisement

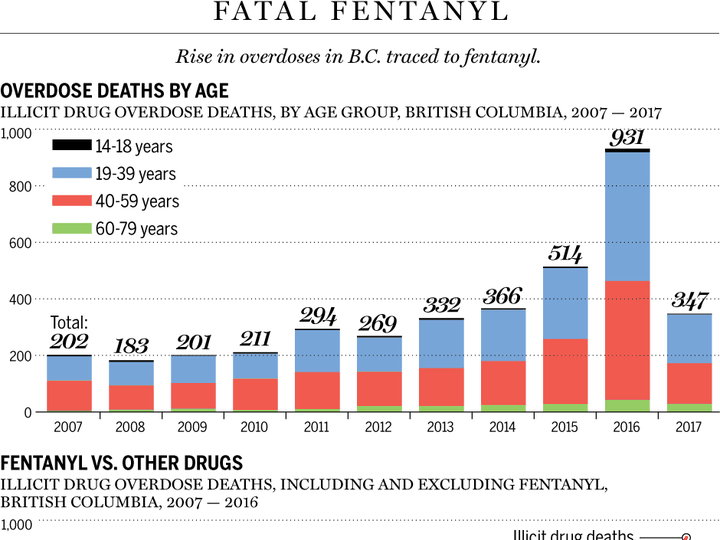

and a new report out this week from the ontario drug policy research network says fentanyl-related deaths in all age groups in the province has increased 548 per cent between 2006 to 2015.ten per cent of ontario students in grades 7-12 self-reported using a prescription opioid for non-medical reasons at least once during the previous year, according to a 2015 report from the centre for addiction and mental health. four per cent reported using these drugs six times or more in the past year.the numbers could be underestimated, according to the study’s authors. unlike alcohol or marijuana, it is harder for teachers and parents to detect opioid use, “so we are relying more heavily on self-report,” said robert mann, the study’s co-author. while the 2015 version of the study did not ask specifically about fentanyl, this year’s survey, currently underway, will.in british columbia the statistics are especially harsh: there were 12 overdose deaths from illicit drugs among 14-18 year olds in 2016, according to the b.c. coroners service — half of them were confirmed fentanyl-related. final testing could confirm more. there have been two more overdose deaths in that age group as of march 31 this year.rashmi chadha, an addictions physician with vancouver coastal health, said some young people start using opioids for pain, but they can quickly become dependent on them.“many of the young adults that i see are actively seeking fentanyl over heroin. one 17-year-old girl had received a large dispense of oxycodone from her surgeon for pain following cosmetic surgery,” chadha said. “she began refilling it every two weeks, saying she had ongoing pain, but confided that she was really using it for sleep and to share with her friends to get high. she was cut off by her doctor after about a month, then developed opioid withdrawal and ended up buying it on the street.“over time oxycodone became too expensive so she turned to cheaper heroin and fentanyl,” chadha said.it is an unfortunate twist of nature that while the young brain is developing it is also more vulnerable to becoming addicted.the adolescent-young adult period is a key transitional period for the brain. brain cells — “neurons” — are pruning, where some connections are kept and others dissolve. white matter volume increases and becomes more organized. grey matter — the cell bodies themselves — decreases.the largest change is the development of the prefrontal cortex. this is the part of the brain involved in executive functioning — “higher order” functions like decision-making. the prefrontal cortex helps override impulsivity when it comes to risk-taking, but typically is not fully developed until after age 25.“simply put, the teen brain is not the adult brain,” said sion harris, the co-director of the center for adolescent substance abuse research at boston children’s hospital.“through adolescence into the mid-20s, our brain gradually strengthens our ability to self-reflect, organize towards goals, plan out steps towards those goals, and perhaps more importantly, inhibit impulses that aren’t the wisest and regulate emotions – basically, things we would associate with a mature adult,” harris explained.“i talk to parents all the time and say, ‘you still need to be (your teens’) prefrontal cortex during this time,’ ” harris said.marisa silveri is a professor of psychiatry and a neuroscientist at boston’s mclean hospital and harvard medical school, who focuses on adolescent brain development, specifically risk factors for substance abuse. “while there are no published neuroimaging studies on fentanyl and the teen brain, we can see from research on oxycodone that these opioids decrease the connectivity in the prefrontal cortex and alter the thickness of the cortex,” silveri said.therein lies the vicious cycle: adolescents have a still-developing prefrontal cortex, which can facilitate drug-seeking behaviour. the drug then alters the development of this area of the brain.and opioids, especially fentanyl, are powerfully addictive. they act on special opioid receptors in the brain, and the strength of the opioid depends largely on two things: how quickly it reaches the brain once it’s in the blood; and how tightly it binds to the “mu” opioid receptor, which regulates the reward pathway of the brain.“we know that fentanyl binds very tightly to the opioid receptor and it permeates the blood-brain barrier quickly. all this translates to a small dose of the drug having a huge effect. essentially, you would need 40- to 50- times more heroin to get the same effect,” explained hakique virani, a public health and addictions medicine specialist at the university of alberta.

addiction, health and law-enforcement officials are becoming increasingly more aware of the presence and danger of fentanyl, a prescription painkiller that has made its way into the illicit drug market as a cheap product for dealers to sell, and a powerful high for addicts to chase. a bag of fentanyl pills.

file/ hand out/edmonton sun/postmedia

advertisement

a stronger version of fentanyl, called carfentanil, is now becoming more accessible, he said. it binds even more tightly to the opioid receptors and reaches the brain more rapidly than fentanyl.fair vassoler, a neuroscientist at tufts university, studies the effects of opioids on rats. “we have to remember that our bodies make opioids — the ‘feel good endorphins’ from pleasurable activities for instance. they help us deal with stress, and bind to these receptors we have in the brain. these external drugs can alter that,” she said.since there is limited information around fentanyl and the brain, especially the teenage brain, researchers and physicians are forced to extrapolate from existing research, mainly around oxycodone and heroin.this is a problem, said scott hadland, a specialist in adolescent and addiction medicine specialist at boston medical center. “(u.s.) studies of teens show a decline in experimenting with opioids, but an increase in the risk of overdose, which in part may be due to fentanyl making its way into the drug supply,” he said.hadland said some teens in his clinic recalled knowing at an early age about vulnerabilities they have towards opioids. “in my practice it’s common to have a 15- or 16-year-old with opioid addiction tell me they remember having a different experience with codeine in cough syrup when they were a child, that they could feel it affected them more than other kids,” he said.“those of us who are pediatric addiction specialists know that one of the most important things we can do is intervene quickly when early signs of addiction are present,” hadland said.part of the problem with that is the symptoms of opioid drug use are not as obvious to parents and teachers and caregivers as they are with alcohol or other drugs such as marijuana or crystal meth, a highly addictive stimulant. among some of the symptoms of fentanyl and other opioids are drowsiness, confusion, constipation, nausea. at higher doses it can slow down or stop breathing.in an overdose, pupils becomes smaller (pinpoint pupils), the victim becomes unconscious and breathing stops (respiratory depression). these are referred to as the “opioid overdose triad.”hadland advises parents to take general preventative measures – locking up prescription medications, disposing medications that are not needed and maintaining open lines of communication.“rather than jumping in and asking a teen directly whether they’ve used substances, it may be easier for parents to start the conversation by first asking what they are seeing in school among their peers – that gives a sense of their risk environment, and is a nice opener to a discussion in which a parent can then find out whether their teen has used substances.”sandi shaver agrees. since cameron died, she’s helping others through her work as a mentor for street youth at circle of care in winnipeg. “many of these kids want to stop but don’t know how.”amitha kalaichandran is a pediatrics resident and fellow in global journalism at the munk school of global affairs.

7 minute read

7 minute read